Unpredictable extreme weather and a population boom prompt some coastal residents to look for new hope away from the water. As unpredictable extreme weather and a population boom make fishing more difficult, families hope for a way out.

Out at sea, soft waves pressed and seesawed Sorm Doeun’s boat as he took a careful drag of his cigarette without shifting the rudder. He kept the craft steady for his weary son, who was napping in the bow after a morning casting nets.

Along the coast, duos of volunteers carefully brought containers filled with crab eggs to the shoreline. Ung Bun, manager of a “crab bank” programme, released eggs from pregnant crabs to bolster wild populations and boost local catches.

Inside a home, plastic coiled around her big toe as Tan Leakhena masterfully wove metres-worth of fishing net. Watching over two of her three children, who were too young to help, Leakhena’s hands remained a blur for most of the afternoon.

These episodes of experiences have occured daily for years at Angkol village in the southern Cambodian province of Kep. But these mundane moments at Angkol Beach are on the verge of change as residents – tired of coping with climate change and unpredictable extreme weather – consider land offers.

“I will sell my land once the price is right,” Sorm said. “I am a fisherman because I had no other options, but life like this is too hard. I don’t want my kids to be like me. That’s why it would be good to sell.”

Despite the establishment of a community fisheries committee and the development of sustainability initiatives, a consistent lack of funding has dwarfed potential growth, adding to the list of reasons fishing families are open to selling land. Most residents, like Doeun, have little interest in who is buying the land and what development might take place.

To document a fading way of life in Kep, Southeast Asia Globe spent a week among the roughly 200 families of Angkol Beach and experienced what may be one of the last fishing seasons for some Angkol villagers.

~ ~ ~

At midday, the father and son duo of Sorm and Kli Doeun set out to the sea. The fishermen spend most afternoons casting nets, often returning past midnight to collect their catch. While Sorm has fished since childhood, he said he hopes none of his four children follow his path.

“This work is too hard and too unpredictable,” said Sorm, who never attended school. “I don’t want [Kli] to be a fisherman, like me, he has choices. I am pushing him towards doing vocational training.”

While erratic fishing income is a primary concern, Sorm said “it is also becoming more and more dangerous during rainy season” with strong winds and sea storms limiting the number of days he can venture out to cast nets.

A World Bank climate risk report on Cambodia in 2021 stated the Kingdom’s coastal zones were exposed to “cyclone and tsunami-induced storm surge” and the way climate change could impact these natural disasters was “poorly understood.”

While the effect of climate change on storm surges is uncertain, a baseline study by the Consortium for Sustainable Alternatives and Voice for Equitable Development, which interviewed residents across four coastal provinces, found many respondents had a good understanding of climate change’s impact on them. Storms and floods could damage homes, crops and boats, make fishing more difficult, stop construction and interrupt sales.

“I don’t know how to do any other jobs, so I will keep fishing,” Sorm said. “But my kids don’t have to.”

~ ~ ~

Tan Leakhena is a skilled multitasker. As a mother of three children aged 8, 5 and 1, Leakhena balances caring for her kids with weaving metres of fishing nets for her husband.

This division of labour between genders is common in Angkol village. Leakhena’s sister in law, Sok Korn, performs the same task next door.

Leakhena is undecided about the area’s potential development. It may raise prices for catches and eventually lead to an even bigger land offer, but also could create more traffic and endanger her small kids while they play outside. Without a clear idea of the type and timing of potential development, debating the merits of the situation is as helpful as a torn fishing net.

“I don’t know how I would improve my livelihood, I guess we will see what happens,” said Leakhena, who was never able to attend school, as her focus drifted back to the net she was mending.

Returning to shore with their haul, fishermen are often greeted with a gaggle of eager buyers. Lim Mao, who has been a saleswoman for more than a decade, buys fresh crab and fish before making deliveries to nearby restaurants and markets. On a given Thursday in early May, Mao bought approximately 20 kilograms (44 pounds) of crab for 30,000 riel ($7.40) per kilo.

~ ~ ~

Crab is a big deal in Kep. While the crustaceans have become a pillar of local businesses and livelihoods, they also have become part of the coastal community culture. Near one of the province’s main highways stands a statue of a Krung Kep Blue Swimmer Crab, known as a kdam ses in the Khmer language.

~ ~ ~

Unpredictable extreme weather increases the danger of venturing long distances from shore and growing human populations add additional stress to wild crab populations. In response, the Angkol community fisheries committee, with the help of NGOs, developed a sustainable-use “crab bank” programme.

Bun, Leakhena’s brother and Korn’s husband, manages the programme by protecting pregnant crabs caught by fishermen and donated to the crab bank.

~ ~ ~

Every week or so, Bun enlists the help of several volunteers to release the eggs into a nearby sea protection zone just off the coast of Angkol Beach. They hope the released eggs will safely grow into crabs and later be caught near the shoreline.

~ ~ ~

Even though fishermen like Sorm and Bun are happy to have a working crab bank, Doeun said most families still hope for a way out of the difficult life they said fishing has become.

As tourism in Kep booms as Cambodia continues to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, the province will likely continue to undergo development by the government and real estate firms. Most area landowners are content with this prospect as long as the price is right. The identity of buyers and the potential developments are nothing more than a passing curiosity.

~ ~ ~

Meas Va, the Community Fisheries Committee chief and a commune council member, sold his coastal property and constructed a house further inland, predicting most residents will likely follow suit.

“Most of the villagers are poor and daily earnings always change,” Va said. “When bad climates cause bad catches, it can get very bad for families. That is why most are open to selling.”

Despite not knowing if an environmental impact assessment was conducted, Va confidently said any development, tourism or otherwise, would not impact the sea protection zone where the crabs are released.

An Reaksmey isn’t so sure.

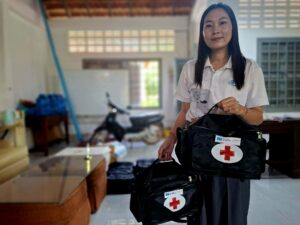

The decrepit crab release station allows pregnant crabs to be lowered into a net and release eggs directly into the ocean, cutting the burden and costs of safeguarding pregnant crabs and later releasing eggs. But the repair and security costs for the station are far beyond the committee’s budget.

“I want to keep developing this programme so we can save and release more pregnant crabs and eggs, and maybe even create a fish bank,” Reaksmey said. “But it is just too expensive.”

Without growth potential, Reaksmey believes fishing families in Angkol Beach and across Kep will continue migrating away from the coast and a livelihood at sea.

For the last three years, Reaksmey has been in charge of the crab bank and is disappointed that it hasn’t grown. The only female member of the Community Fisheries Committee, her dream for the programme stands on stilts a few metres from shore.

Photos by Anton L. Delgado for Southeast Asia Globe

(Article was published on GLOBE / Publication date 08 June 2022)