Evidently, socio-economic disparities that were established during the colonial period persist in the postcolonial era. In this blog post, I clarify how colonial legacies have a significant role in perpetuating injustice. I contend that the unequal systems of education contribute to segregation since they entrench exclusions and stigmatize people who are denied access to it. My objective is to think – or re-think from a postcolonial perspective – potential solutions to guarantee the right to education.

Injustice in education is a major concern for the French NGO Action Education / Aide et Action (AEA), which I work for in Cambodia. According to data from UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank, there are significant disparities between the Global North and the Global South. Although global education inequity is well acknowledged, its colonial roots might not be as well known. Without denying the Khmer Rouge’s legacy, which had a devastating impact on Cambodia’s education system, disrupting education and leaving long-term effects, I consider it as a partial explanation.

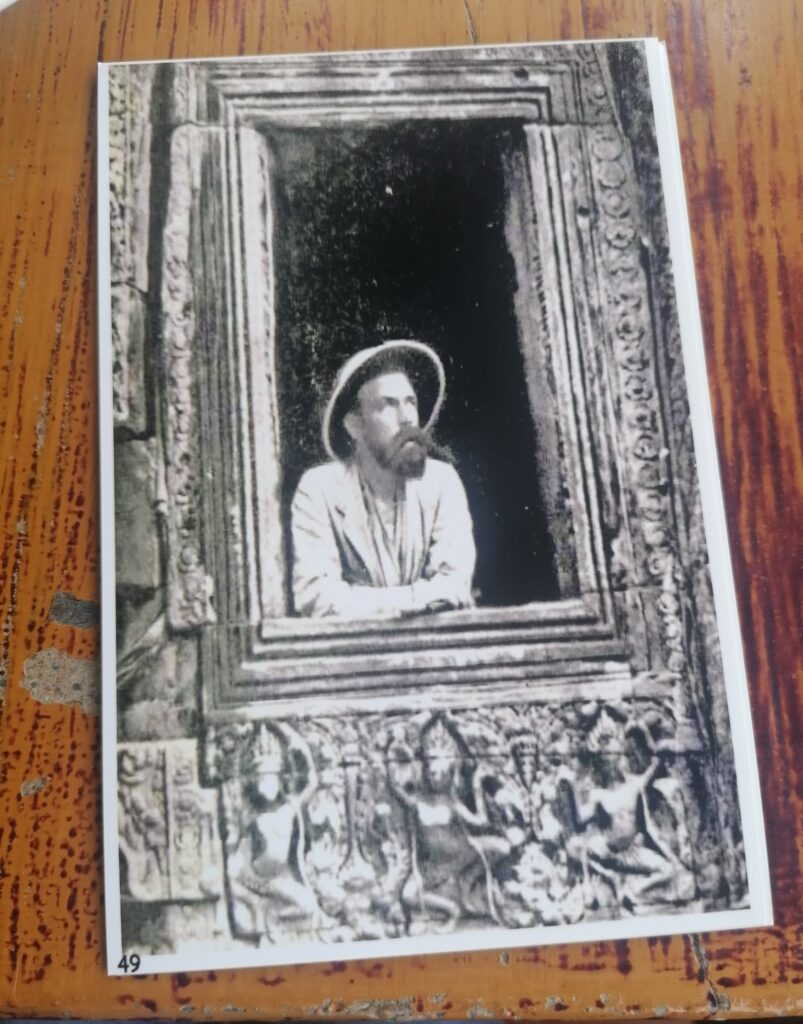

I chose to focus instead on colonial history. The reason is that the Cambodian education system, like many in former colonies, was shaped by colonial powers. Education served as a strategic instrument to further the colonialist agenda at the expense of equity. Many historians claimed that the colonial system of education was based on segregation and exclusion. Indeed, only a small percentage of Cambodian students attended French schools. The colonialists feared that “educating savages” would endanger their rule and authority, which is why they did not see any value in educating the masses.

Rather, they chose to concentrate on providing an elitist education, designed to empower their own children and, the children of a few privileged locals. The goal was to create a local elite to assist in the colonial administration, rather than to give everyone equal access to education. Ideologically, colonialism was was about condemning all that was native and, imposing a “civilised” way of life. Education was used as a political tool to teach the glory of the French empire and, to spread the French language and culture in Indochina.

A colonial legacy: Global and national inequality

Today, it must be acknowledged that there is still a very small percentage of Cambodian students that attend French education. I argue current inequities can be traced back to the colonial administration’s way to design and establish educational systems. Supporting my claim that one of the enduring effects of colonialism and colonization is educational inequality, I point out that a centuries-old, largely Eurocentric mindset maintains global disparities by asserting the supremacy of education in France and other Western countries, while the inherited system in Cambodia continues to disadvantage the majority of people.

Indeed, there is a number of colonial legacies that make difficult or impossible for the average Cambodian to benefit from French education. First, French academic institutions may not fully or officially recognize Cambodian academic qualifications. Second, education fees are high, especially for non-EU nationals, as well as living expenses and travel to Europe, which are not affordable for the majority of Cambodians. Third, obtaining a student visa can prove difficult due to Europe’s racist and disgraceful policies of immigration.

In Cambodia, it is fair to mention that there has been important progress, which AEA participated to, including increasing enrolment and literacy rates, improving school infrastructures, and improving teacher training. Nonetheless, the colonial educational system is partly responsible for socio-economic inequalities within the country. Major challenges remain: urban-rural disparities, economic barriers – many families are impoverished – and limited access to early childhood education.

Quality education for all: An anti-colonial solution

Driven by an anti-colonial impulse of resistance to injustice, I think it is important to consider how education contributes to the perpetuation of social inequality and, consequently, how it may be used to challenge it. Like many other NGOs, AEA works to address structural problems that are the primary drivers of inequality, such as poverty, discrimination and inadequate infrastructures. Prioritizing the most vulnerable populations is AEA’s main approach to ensure an equitable access to quality education for all.

This approach aligns well with the anti-colonial line of thinking, most likely inadvertently. A strategy that focuses on systemic disparities in educational resources might successfully contribute to close the gap between privileged and marginalized communities. Promoting a more equitable distribution of resources is work towards rectifying past injustice. Disparities often reflect colonial-era practices of inequality, which favoured the wealthy and urban centre over rural and remote areas.

An additional way to address long-standing issues rooted in historical injustice is to advance inclusive education. To ensure that our activities align with and respect the needs and beliefs of local communities, we place a strong emphasis on community engagement. AEA’s work also focuses on improving educational access for marginalized children, including students with disabilities and those from difficult socio-economic backgrounds.

Since we are a French NGO that receives co-funding from the EU, it is particularly important for us to not impose the French language or alter the curriculum in Cambodian schools. Rather, we design our projects in accordance with the Government’s national programme. AEA’s projects to incorporate information and communication technology (ICT) into schools, for instance, are part of larger efforts to address the increased need for technology access and digital literacy. The governmental plan is to enhance educational outcomes by incorporating technology into the national education system.

Digital literacy: An anti-colonial tool

A anti-colonial strategy to address the divide between wealthier (Global North) and poorer (Global South) regions supports innovative educational approaches that address local challenges. This includes integrating technology in ways that are accessible and beneficial to students in the Global South. From my postcolonial perspective, I approach digital literacy as a key tool to promote critical thinking and decolonize the systems of education.

Access to a wide range of resources and points of view outside conventional textbooks, including local knowledge, alternative historical accounts, and diverse cultural perspectives, is made possible by digital literacy. A broad access to the Internet encourages students to evaluate information from multiple sources and to question rather than passively receive information. As a result, students can learn to critique dominant narratives, such as Eurocentric views of the world for example.

Then, I suggest that a decolonial education recognizes, values, and promotes local knowledge, ecological expertise from the ground, and traditional or cultural practices. It involves learning to consider multiple perspectives, especially those of marginalized people in society, such as ethnic groups or people living with a disability. Marginalized communities may share their own stories, knowledge, and perspectives through digital platforms. Digital education empowers them to represent their voices and to be heard.

Finally, digital inclusion promotes mutual learning between people from different countries, rather than perpetuate neo-colonial patterns. Digital tools facilitate international collaboration and fosters global awareness and cross-cultural exchanges. In general terms, education can help students to understand historical and contemporary issues. It can play a role in addressing historical injustice, which involves teaching about past atrocities, as well as discussing their ongoing impacts and exploring ways to address them.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog post are postcolonial and those of the author Dr. Cindy Cao. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of AEA or its partners.