Access to clean water is a fundamental human right, yet inequalities persist both locally and globally. In this blog post, I provide a postcolonial perspective on water injustice, using the example of Kep in Cambodia to highlight the system which perpetuates environmental and socio-economic disparities. The purpose is to identify potential solutions for water justice.

People in the Global South, especially the poorest segments of the population, are most vulnerable to climate change, even if rich countries of the Global North are mostly responsible for it. Climate injustice and social injustice are both drivers of water-related challenges. On one hand, changes in rainfall patterns and rising temperatures pose a threat to water resources, with little improvement in sight owing to the predictable effects of climate change. On the other hand, economic growth increases demand for water and energy, which exacerbates water scarcity and pollution.

In other words, water problems make existing inequalities worse. In turn, socio-economic disparities exacerbate environmental issues, as poverty impedes environmental conservation and protection. How can the vicious cycle be broken? I argue that studying French colonialism in Indochina and its current repercussions in Cambodia is a valuable exercise in identifying potential solutions and alternative models of development.

Cambodia is an interesting case because it is one of the countries in the world that has made the most progress in terms of providing its population with access to clean water, but significant inequalities continue to endanger populations and the environment. Let me take Kep, the touristic beach town where I live, as an example of water inequality.

On one hand, luxurious boutique hotels and resorts consume a lot of clean water for non-essential purposes – such as filling their big swimming pools or irrigating their private gardens – while portraying themselves as “green” through advertising. On the other hand, fishing communities consume far less clean water, when they have access to it, for vital needs such as drinking and washing, since they belong to lower socio-economic groups.

Although water injustice is undeniable, it is not always visible. High-end resorts may appear clean in the eyes of tourists but, they are not environmentally clean. In contrast, community businesses use much less water, making them substantially greener. Despite this important comparative advantage, fishing communities, which are affected by poverty, social marginalization, and climate change, face unfair competition when they attempt to make a livelihood in the industry of tourism. Small Cambodian businesses do not benefit from the same access to the digital world and, do not have any funding for marketing to attract international tourists.

Learn from the past. Understand the present. Envision the future

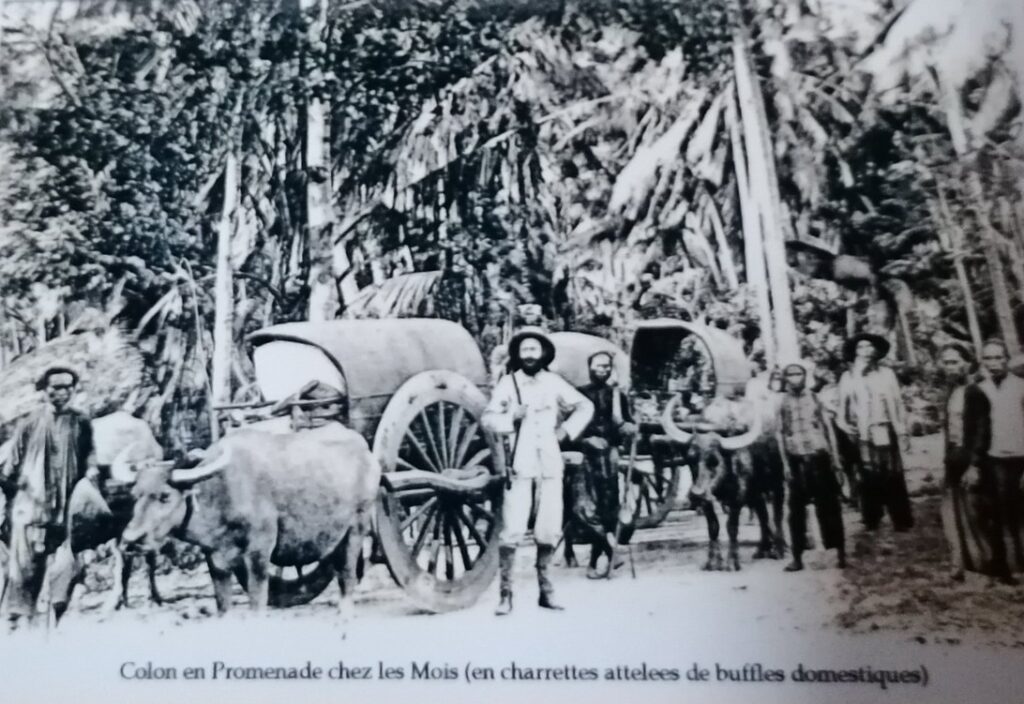

Postcolonial theorists often explore the colonial past in the neo-colonial present to explain injustice and inequality. Considering both questions of water and tourism are embedded in power structures, I argue unequal dynamics between local communities and expatriate business managers are rooted in history and, more precisely, in power relations between colonizers and colonized.

Historically, French colonialists established “Kep-Sur-Mer” in 1908 as a beach resort for the wealthy, while the majority of the people was exploited and kept in poverty. Today, many foreign-run enterprises, such as luxurious French boutique hotels, continue to make economic profit without equitable sharing of benefits to the surrounding populations. Therefore, a colonial-style system of tourism continues to perpetuate and, to exacerbate inequality issues.

The colonial society, which was predicated on the exclusion, segregation, and marginalisation of the disadvantaged classes, is the historical foundation for foreign economic elites to maintain the neo-colonial system of tourism they benefit from and, their privileges. Considering this system gave rise to and sustained the contemporary reality of water injustice, it stands to reason that the most unsustainable scenario for the future would be one that foresees an increase of inequality.

The first solution is to provide support at the grassroots level. The CO-SAVED initiative, co-funded by the EU and co-led by the French NGO Action Education / Aide et Action (AEA), directly contributes to the building and/or rehabilitation of water infrastructures in schools and remote villages. The second solution is to promote change among the affluent through advocacy and awareness-raising activities. To reduce water waste, privileged people should change their lifestyles, limit their water consumption, and equally distribute money and water resources.

Responsible tourism: For people and planet

In Cambodia’s coastal provinces, AEA promotes responsible tourism, which is an alternative model of tourism development to address inequities. In general terms, responsible tourism is concerned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an equitable economic development, a sustainable use of natural resources and, poverty reduction. It is based on the belief that tourism has the potential to conserve, protect, and promote the local culture and the environment, as well as to empower marginalized and/or remote communities on a social and economic level.

However, when tourism is dominated by foreign-run and luxurious businesses, economic benefits leak from the local economy. Indeed, the development of tourism in Kep has provided so far relatively little economic profit to native communities. Consequently, an important agenda is to re-think and to re-define tourism in order to prioritize the rights of local people over the rights of tourism corporates to make profit.

It is time to move forward with a community-based and green model of economic development. Thus, it is now essential for community members and community businesses to increasingly impose themselves in the tourism market. AEA’s ambition is to empower sea-oriented communities through training, education and knowledge acquisition. The purpose is to increase green and responsible tourism opportunities and, to re-balance power inequities, whether environmental, economic or cultural.

We have to raise the voices of the impoverished, oppressed, and voiceless. Local communities have significant potential for rebalancing historical power relations. For example, native communities and local tour guides offer their unique perspectives on their natural environment and history. Their vision may call into question the image of Kep that dominant actors in tourism have created and conveyed via promotional materials.

I believe that international tourists, such as the French, are unlikely to perceive a guided tour as a threat to their national identities. Instead, tourism and a discussion about a shared colonial history may provide a chance to promote local cultures, boost people-to-people encounters, and foster mutual understanding.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog post are postcolonial and those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of AEA or its partners.